Because of popular demand, Dr. Morganson and I decided to make this important post available to PainDr.com blog followers. This article was written collaboratively with Daralyn A Morgenson BS, PharmD. whose biosketch appears below.

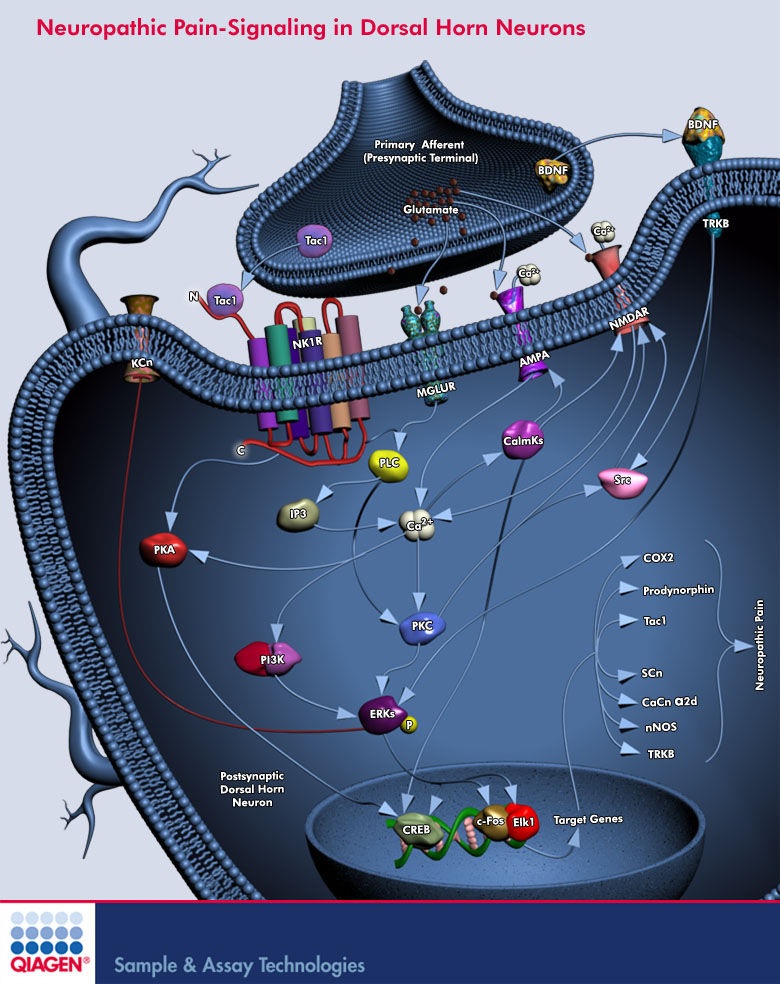

Neuropathic pain causes significant morbidity in the United States.

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy is estimated at about 2.4% of the population.1 Of the 14 million US individuals with diabetes, roughly 25% experience painful diabetic neuropathy.

Despite advances in vaccination for varicella zoster virus, around 25% of patients with a herpes zoster infection will develop persistent neuropathic pain.2 More than 85% of patients with neuropathic pain caused by peripheral neuropathy will require pharmacotherapy.

Unfortunately, there are few head-to-head trials comparing agents for neuropathic pain, so selecting the best option can be difficult.

Pregabalin and gabapentin are often considered first-line treatments for various neuropathic pain syndromes, generally irrespective of cause.1 Because the products are so variable, this article compares the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of pregabalin with various gabapentin formulations, and also covers conversion regimens.

Pharmacokinetics of pregabalin and gabapentin

Both pregabalin and gabapentin are antiepileptic medications that bare structural resemblance to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), though neither agent has activity in GABA’s neuronal systems.

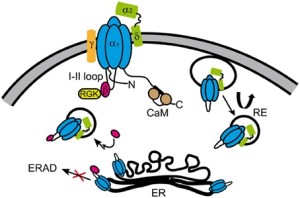

Although the exact mechanism of action is somewhat unclear, the drugs’ efficacy in neuropathic pain is linked to their ability to bind to voltage-gated calcium channels in the central nervous system (CNS), specifically to the alpha-2-delta protein. This binding decreases neurotransmitter release in the CNS as a result of reduced calcium influx through the gated channels.3

Gabapentin is indicated as adjunct therapy for partial seizures and postherpetic neuralgia.4 Pregabalin is indicated for the same uses as gabapentin, plus the management of fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain associated with diabetes, specifically diabetic neuropathy.5

Overall, the pharmacokinetic profiles of these 2 medications are somewhat similar, but they also have some significant differences.

For example, both drugs are structurally similar to the amino acid leucine. Because of this, they can both undergo facilitated transport across cellular membranes through system L-amino acid transporters.3 This is the major form of absorption for gabapentin and pregabalin, with the exception of an extended-release gabapentin prodrug to be discussed later.

However, pregabalin may either have an additional system of absorption or be better transported than gabapentin, as it is almost completely absorbed, while gabapentin is not. In addition, absorption of gabapentin is limited to the small intestine, while pregabalin is absorbed throughout the small intestine and extending to the ascending colon.

Gabapentin is more slowly and variably absorbed, with peak plasma concentrations around 3 hours post-dose. Pregabalin is quickly absorbed, with the maximum rate of absorption being 3 times that of gabapentin. It reaches peak blood concentrations within an hour after ingestion.

Absorption of gabapentin is saturable, leading to a non-linear pharmacokinetic profile. As gabapentin doses increase, the area under the curve (AUC) does not follow proportionally. Unlike gabapentin, absorption of pregabalin is not saturable, and the drug has a linear pharmacokinetic profile.

The bioavailability of generic gabapentin in tablet and capsule formulations equivalent to brand-name Neurontin is about 80% at lower doses such as 100 mg every 8 hours, but only 27% bioavailable at doses of 1600 mg every 8 hours.3,4 This differs greatly from pregabalin, which boasts a greater than 90% bioavailability across a dosage range from 75 mg to 900 mg daily in divided doses.3

Gabapentin’s bioavailability for its intended patient population is also more variable than pregabalin’s bioavailability. Variability among patients is believed to be 10% to 15% with pregabalin and 20% to 30% with gabapentin.3

Finally, food increases the AUC of gabapentin by about 10%, with no change in time to maximum concentration (tmax). In contrast, the AUC of pregabalin is unaffected by food, though absorption is slower.3

Distribution of gabapentin and pregabalin is very similar. Neither agent is bound by great extent to any plasma proteins, decreasing the likelihood of drug interactions due to protein binding. Both have high aqueous solubility, and the volume of distribution of each is similar (0.8 L/kg and 0.5 L/kg for gabapentin and pregabalin, respectively).3

Drug-drug interactions are unlikely for both pregabalin and gabapentin. Neither pregabalin nor gabapentin is affected by cytochrome (CYP) drug interactions, as neither drug is metabolized by CYP enzymes. Both undergo metabolism to a negligible extent (<1%).

Renal excretion is the major method of both drugs’ elimination from the body. Agents that decrease small bowel motility can theoretically cause an increase in the absorption of gabapentin, because it is not completely absorbed. However, as pregabalin is more than 90% absorbed, its absorption is not affected by changes in small bowel motility.3

Gabapentin formulations

Gabapentin is also available in 2 extended-release formulations: a tablet (Gralise) and a gastro-retentive prodrug, gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant).

Both have different pharmacokinetics and are not interchangeable with standard formulations, the original of which is Neurontin. Side effects of these newer formulations are similar to standard formulations.6,7

Gralise is indicated for postherpetic neuralgia and taken as an 1800 mg maintenance dose once a day. The AUC of 1800 mg of Gralise is slightly less than 1800 mg of the standard formulation. In addition, the average maximum concentration (Cmax) of Gralise is slightly higher than 1800 mg of the standard form, and minimum concentration (Cmin) is slightly lower. Finally, Tmax is increased in the extended-release form.

Although food does not palpably affect the AUC of standard forms of gabapentin, Gralise should be taken with food because the bioavailability is greatly increased (33% to 118%, depending on the meal’s fat content).6

Horizant is a prodrug of gabapentin indicated for postherpetic neuralgia and restless leg syndrome. The recommended maintenance dose is 600 mg twice a day. Doses greater than 1200 mg daily are not recommended, as side effects increase without a corresponding increase in efficacy.7

Bioavailability of gabapentin enacarbil is about 75%, which is somewhat improved over the standard formulation. It is absorbed through the small intestine through a proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter (MCT-1).

Unlike the original formulation, absorption of gabapentin enacarbil is not saturated at high doses, as MCT-1 is expressed in high levels in the intestinal tract. The drug undergoes near-complete first pass hydrolysis to gabapentin by non-specific carboxylesterases mainly in enterocytes, as well as in the liver to a lessor degree.

Consumption of alcohol increases the release of gabapentin enacarbil from the extended-release tablet. Therefore, alcohol should be avoided when taking Horizant due to increased risk of side effects.7

Like standard formulations of gabapentin, Gralise and Horizant are not metabolized to an appreciable extent by phase I metabolism, and they are neither a substrate nor an inhibitor of p-glycoprotein. All forms of gabapentin must be adjusted in renal dysfunction, similar to standard formulations.6,7

One review found that these extended-release formulations have similar efficacy to standard ones, and they might also have fewer adverse events.8

Both pregabalin and gabapentin are well tolerated. Dizziness and somnolence are the most common side effects in both drugs (>20% seen in gabapentin).3-5 Confusion and peripheral edema have also been reported with gabapentin.4

With both drugs, side effects are dose dependent and reversible if the medication is discontinued.3 The abrupt discontinuation of any form of gabapentin is not recommended because withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, nausea, pain, and sweating may present. When discontinuing gabapentin it is recommended to taper the dose over a week at least.

As with all antiepileptic drugs, increased risk of suicidal ideation is possible.4,5

Pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin

Gabapentin and pregabalin vary in terms of binding affinity and potency. Pregabalin has an increased binding affinity for the alpha-2-delta protein and is a more potent analgesic in neuropathic pain compared with gabapentin.3

One study developed a population pharmacokinetic model comparing pregabalin with gabapentin.9 The authors calculated values for the concentration of the drug that will give one-half the maximum pharmacologic response (EC50) and used these values to assess potency of the 2 medications.

Based on studies of gabapentin and pregabalin in epilepsy, the EC50 values of pregabalin and gabapentin were estimated to be about 9.77 mg/mL and 23.9 mg/mL, respectively.9 From these data, pregabalin was estimated to be about 2.4 times more potent. For neuropathic pain, pregabalin’s potency ratio may be even greater.

Using studies in postherpetic neuralgia, the EC50 values of pregabalin and gabapentin were estimated to be about 4.21 mg/mL and 11.7 mg/mL, respectively. Based on these values, pregabalin was estimated to be about 2.8 times more potent than gabapentin.9

Pregabalin and gabapentin differ somewhat in terms of their dose-response curves.

One study analyzed data from phase 2 trials of gabapentin and pregabalin and created a pharmacodynamic model.3 The authors found that in patients with postherpetic neuralgia, mean pain scores decreased as the dose of both gabapentin and pregabalin increased.

However, the study also uncovered a plateau of gabapentin’s effect on reducing pain at around 3600 mg/day. In contrast, the pain-relieving effect of pregabalin continued to increase up to the maximum dose of 450 mg/day.3

Pregabalin also exhibited a steeper dose-response curve than gabapentin. Based on the dose-response curves predicted in this model, a dose of 450 mg/day of pregabalin equates to about 3600 mg/day of gabapentin.3

Converting from gabapentin to pregabalin

For clinicians who wish to convert patients from gabapentin to pregabalin, there are a few studies that reviewed such a conversion.

One cohort study reviewed the utility of switching patients with neuropathic pain due to peripheral neuropathy from gabapentin to pregabalin.10 The study followed patients who were switched from gabapentin to pregabalin and then compared them to those who stayed on gabapentin. The authors also stratified the pregabalin group further into those who responded well or poorly to gabapentin, with gabapentin stopped after the nighttime dose and pregabalin started the following morning.

Dosages were switched using the following algorithm:

- Gabapentin ≤900 mg/day → pregabalin 150mg/day

- Gabapentin 901 mg/day to 1500 mg/day → pregabalin 225 mg/day

- Gabapentin 1501 mg/day 2100 mg/day → pregabalin 300 mg/day

- Gabapentin 2101 mg/day 2700 mg/day → pregabalin 450 mg/day

- Gabapentin >2700 mg/day → pregabalin 600 mg/day

This rapid change was generally well tolerated by patients.

The authors found that those who responded well to gabapentin and those who did not showed additional benefit with decreased pain when they were switched to pregabalin. Patients taking pregabalin also had improved pain control compared with those who remained on gabapentin.

Switching to pregabalin resulted in improved pain relief and also fewer adverse events. This was particularly true for patients who previously responded to gabapentin.

Patients who experienced adverse events with gabapentin were more likely to also experience adverse events with pregabalin. These patients were also more likely to discontinue use of pregabalin than those who responded well to both gabapentin and pregabalin.10

Another small trial compared the degree of pain relief with gabapentin to pregabalin in patients with postherpetic neuralgia in order to more closely determine equivalent dosing between the 2 medications.11

Patients were switched from gabapentin to pregabalin using one-sixth the dose of gabapentin with unchanged dosage frequency. After switching medications, patients reported similar pain relief and side effects, with the exception of an increased incidence of peripheral edema in the pregabalin group.

The authors concluded that the analgesic effect of pregabalin was about 6 times that of gabapentin.11

Other studies have looked at methods for converting gabapentin to pregabalin. One such trial used population pharmacokinetic models to examine 2 possible scenarios for converting gabapentin to pregabalin, using a ratio of 6:1 gabapentin to pregabalin.9

The first scenario involved discontinuing gabapentin and immediately starting pregabalin at the next scheduled dosing period. The other option included a gradual transition from gabapentin to pregabalin.

In this second scenario, the gabapentin dose was decreased by 50%, and 50% of the desired pregabalin dose was given concurrently for 4 days. After this time, gabapentin was discontinued and pregabalin was increased to full desired dose.

The model looked at transitioning patients from gabapentin to pregabalin at various doses, including:

- Gabapentin 900 mg/day → pregabalin 150 mg/day

- Gabapentin 1800 mg/day → pregabalin 300 mg/day

- Gabapentin 3600 mg/day → pregabalin 600 mg/day

Both scenarios were quick and seamless, so the authors concluded that either technique could be an effective method to switch patients between the medications.9

Final thoughts

Though pregabalin and gabapentin have somewhat similar pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles, there are clearly significant differences. Overall, pregabalin has more predictable pharmacokinetics, and it also shows a stronger binding affinity to its target receptor, increased potency, and a steeper dose-response curve in neuropathic pain that does not plateau over recommended dosing levels.

A few studies have found that pregabalin has fewer side effects and may be more efficacious for neuropathic pain than gabapentin. Several studies reviewing conversion of gabapentin to pregabalin predict that a rough ratio for conversion is about 6:1 gabapentin to pregabalin. In addition, a direct switch from gabapentin to pregabalin seems to be well tolerated, making the conversion simple.

Clinicians should note that pregabalin has various pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic advantages over gabapentin, and a conversion between the 2 medications is often well tolerated.

As always, comments and experiences are welcome!

Dr. Morgenson received her BS in psychology from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and her PharmD from the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy. She is currently completing a PGY1 pharmacy residency at the Stratton VA Medical Center, with a focus on ambulatory care.

References

- Toth C. Substitution of gabapentin therapy with pregabalin therapy in neuropathic pain due to peripheral neuropathy. Pain Med. 2010;11(3):456-65.

- Blommel ML, Blommel AL. Pregabalin: an antiepileptic agent useful for neuropathic pain. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(14):1475-82.

- Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, Chapel S, Janiczek N, Burger P. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinetics. 2010;49(10):661-9.

- Neurontin [Package insert]. New York, NY: Park-Davis, Division of Pfizer; December 2013.

- Lyrica [Package insert]. New York, NY: Park-Davis, Division of Pfizer; December 2013.

- Horizant [Package insert]. Santa Clara, CA: Xenoport Inc; July 2015.

- Gralise [Package insert]. Newark, CA; May 2014.

- Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Toelle T, Rice AS. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD007938.

- Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, Chapel S, Janiczek N, Burger P. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(10):661-9.

- Toth C. Substitution of gabapentin therapy with pregabalin therapy in neuropathic pain due to peripheral neuropathy. Pain Med. 2010;11(3):456-65.

- Ifuku M, Iseki M, Hidaka I, Morita Y, Komatus S, Inada E. Replacement of gabapentin with pregabalin in postherpetic neuralgia therapy. Pain Med. 2011;12(7):1112-6.

alpha-2-delta schematic above from Source: https://www.google.com/search?q=neuropathic+pain&biw=1018&bih=407&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&sqi=2&ved=0ahUKEwiW6crekqDLAhVD5yYKHRkWCHIQ_AUICCgD#tbm=isch&q=alpha+2+delta+receptors&imgrc=8ysMRJ0z1ta1iM%3A

I’ve taken both gabapentin and Lyrica for neuropathy from spinal cord trauma. They both helped with the unrelenting pain however, they significantly interfered with my memory- Lyrica more so than gabapentin. I couldn’t remember the contents of a short news article five minutes after I read it. I wasn’t able to read books because I couldn’t remember what happened in the previous chapter and I would look at material I had written a year or two before and have no idea what it meant. While taking Lyrica, I lost all motivation to work, go out with friends, or to do basic household chores. I became a brain dead zombie.

I finally decided that I didn’t want to live with the side effects and tapered off 400 mg/day of Lyrica in four months. The withdrawal was beyond hell. I fell into the darkest depression you can imagine, started having massive panic attacks, couldn’t sleep for days then would sleep for 20 hours, and felt like I would crawl out of my skin. Towards the end of my taper, I became suicidal and finally attempted suicide. I made the rounds of all my doctors, asking for help but none of them believed me when I told them how bad the withdrawal was. I begged for help when I became suicidal but nobody cared. I dragged myself out of that hell with no help from anyone, in fact, all I got from pain management doctors was them telling me that I was making all of my symptoms up, that it was all in my head.

A few years later I had a surgery that solved my main source of pain so I tapered off opioids after taking one type or another for four years: 170 mg/day of OxyContin + oxycodone in 5 months. The only withdrawal I experienced was a bit of yawning and watering eyes. A few times I felt a bit jittery but that was it. During the whole process, I kept waiting for the withdrawal to hit, since I’d heard so many horror stories about it but it never came.

I’ve always taken all my medications as prescribed and never abused any of them. In my experience, opioids had minor side effects- they make my thinking a bit darker than usual, though not to the extent that I would be considered depressed. Lyrica stole my mind and my soul and almost cost me my life. Gabapentin also caused side effects and a problematic withdrawal but not as bad as with Lyrica. I’ve heard many similar horror stories, including reports from others who were pressured into taking gabapentin or Lyrica by doctors who are too afraid to prescribe opioids, in fact there is even a Lyrica Survivors group on Facebook for people from all over the world dealing with horrendous side effects and withdrawal from this medication.

Although I went through absolute hell with Lyrica, I would never presume to push to outlaw this medication since I know that there are people that it helps and they don’t have problems with side effects nor withdrawal. I wouldn’t dream to dictate to another, what their doctor should prescribe. For me, opioids are a safe way to control my pain with minimal side effects. The decision for whether I take them or not should remain between me and my doctor. Others who’ve struggled with these meds need to understand that not everyone has their experience and one person’s hell can be another’s savior. For me, opioids were a godsend and got me through the worst pain I have ever experienced, helped me get off of Lyrica, and then, when it was time, they gently let me go.

With regard to neuropathic pain, the first line of treatment should be alpha lipoic acid and B vitamins. There are a number of papers that show that these are both effective in treating neuropathy and, to my knowledge, don’t have significant side effects. I found that they help with my neuropathy to a surprising extent. If the skin is intact and you can point to the pain, Lidoderm patches work extremely well and successfully treated the most excruciating nerve pain I’ve ever experienced taking me from 100 on the 1-10 point pain scale (screaming in agony from anything including the slightest breeze touching my leg) to 0 in a few hours. Gabapentin works for neuropathy but it is currently prescribed far too easily (and often as a replacement for opioids) and many people end up taking it for years because they find the withdrawal unbearable. Because Lyrica can cause major problems, it should be treated with extreme care and should come after other treatments have been tried. As with all medications, there are major differences between individuals and assuming that everyone will respond like the average from a drug trial is a recipe for ruined lives.

All GABAergics seem to cause memory impairment as I’ve been on Alprazolam and Clonazepam(Benzos), gabapentin, pregabalin and phenibut(gabapentinoids). Zolpidem(z-med) and Baclofen(GABAB but basically a gabapentinoid).

I was prescribed pregabalin three years ago to help with the pain from my AS however after just a few weeks I developed gynocamastia which my GP said was a side effect and it should dissappear after I discontinued it.. it’s been 3 years and I still have gyno, my GP has told me I have to pay £4500 to have the gynocamastia removed privately???? Why should I have to pay for this..

I have been on gabapentin (3 × 300mg/day) for about 8 years. It is so very helpful to know the differences between gabapentin and pregabalin. Now I better understand the reason my doctor suggested that I remain on the gabapentin. Another consideration is price – my monthly gabapentin dose costs $5.00 (yes, I have great insurance) while the pregabalin ventures into the upper tier pricing. Thank you for the reprint – I like being an informed user and feel better prepared to work with my doctor regarding my pain.

GREAT piece. Sharing with my doctor.

Thank you so much.

great articles, I have always found you comments to be true in clinical practice. unfortunately, in the real world, most insurance companies want you to write for gabapentin, not pregabalin. They will claim failure on gabapentin is good reason to avoid attempts with pregabalin. perhaps first line of attack should be pregabalin, with a high success rate.

thank, dr. david tarr